Defining the Line Between Representation & Tokenism in Education

Opinion Piece

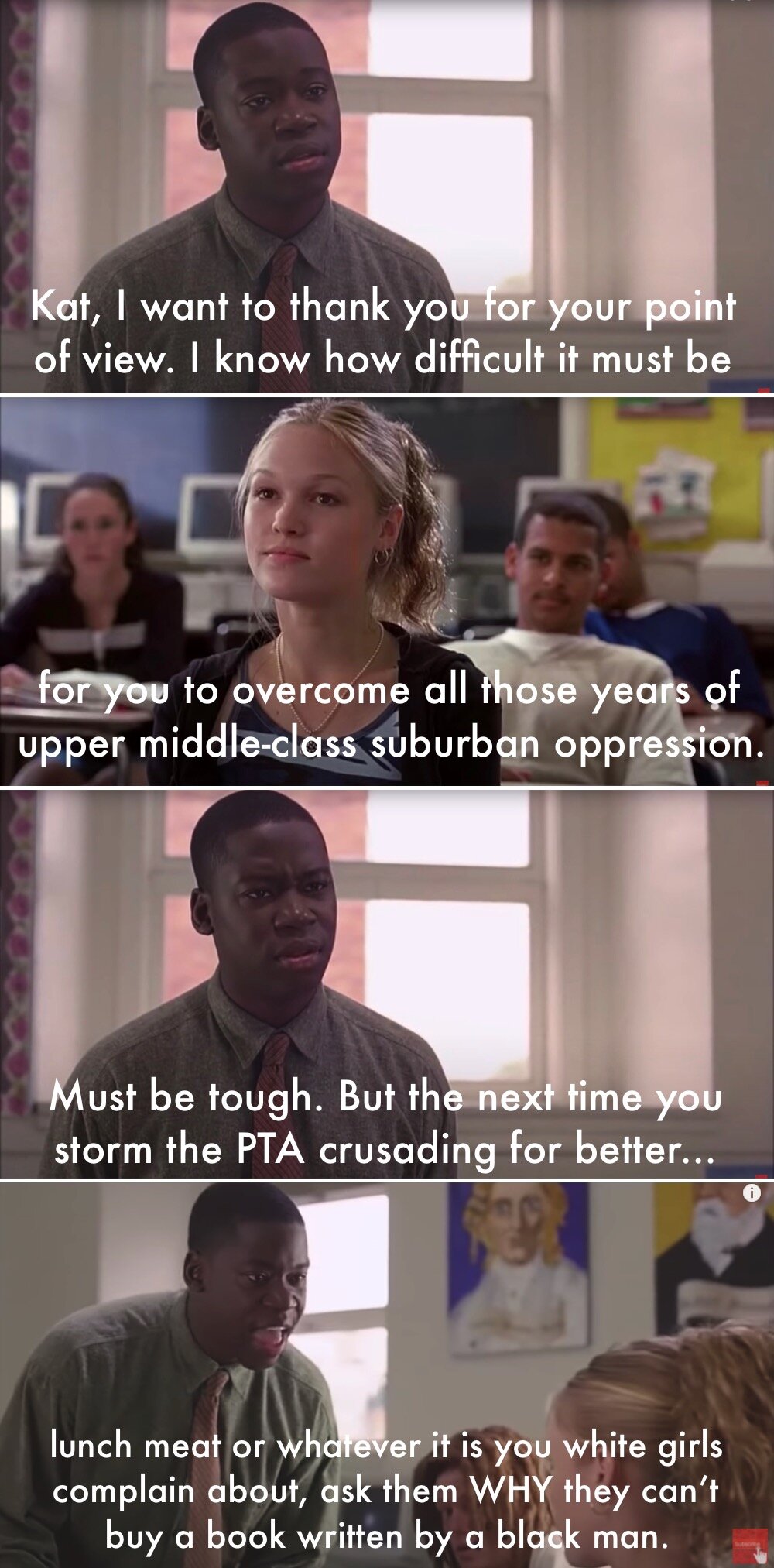

In the 1999 film 10 Things I Hate About You, there’s a brilliant scene (IMHO) in which lead character, Kat (Julia Stiles) complains about the lack of representation of female writers in the English curriculum and points to the ‘oppressive patriarchal values that dictate our education.’ Her teacher, Mr. Morgan (Daryl Mitchell), responds by calling out Kat’s racial and economic privilege and pointing out the lack of representation of black authors in the English curriculum.

Let’s just let the missed opportunity for a discussion of intersectionality pass by here (it was 1999 after all) and focus on the representation issue.

Anyone who has ever been a teacher (or even a pupil) in a high school English department can likely attest to the tendency of old/dead white male authors to dominate the book cupboards and reading lists.

In fact, anyone who’s thought at all about social justice in the context of education will surely have thought about the issue of representation.

Representation is one of the clearest areas for improvement in education. Whether we’re looking at authors of school reading, notable figures taught in history or modern/social studies, or just general depictions in children’s books and other learning materials; it is clear that we need to increase positive representation of people of colour, women, LGBTQIA+ people, people living with disabilities or mental illness, living in poverty, or from any other marginalized or oppressed groups.

So why does representation matter so much?

In Reni Eddo-Lodge’s book, Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race, she describes how, when she was 4 years old, she asked her mother when she would turn white. All the good characters on TV and in books were white and the villains were often black or brown. The (disturbing yet understandable) conclusion she drew from this was that because she was a good person, she would eventually turn white. White was the default and the neutral in the world she saw. Black was an ‘other.’ Eddo-Lodge goes on to say that after finding out (at four years old) that she would never turn white, she learned to find refuge in white British and American fictional characters that she could relate to, because again, the majority of relatable characters were white.

In education, it is not unusual for pupils to see virtually all white characters and role models in their curriculum, teaching faculty, and other learning content found in schools. The impact of this is not only isolating and exclusionary for BIPOC pupils, but it also sends a clear message to all learners that academic excellence and social prestige is generally for white people. This is categorically false and to imply otherwise is harmful to all learners and to society as a whole.

Representation isn’t only about racism. As Kat points out in the scene above, women also tend to be underrepresented, but so do all other marginalized groups including LGBTQIA+ people, those living in poverty, immigrants, refugees, travelers/Roma, and those living with disabilities or mental illness. This sends damaging messages not only to those learners belonging to said underrepresented groups, but also to those in the dominant groups as it reinforces oppressive power structures and beliefs.

It is critical that diversity be represented for learners, and in recent years we have begun to see improvements in representation… Unfortunately, even the best-intentioned attempt at improving representation can sometimes go horribly wrong. This is because attempts at ‘diversification’ and improved representation can quickly become tokenistic and reinforce harmful stereotypes.

So it’s not just a question of quantity of representation, but also quality.

Okay, so what is tokenism?

Tokenism is the practice of making only a perfunctory or symbolic effort to be inclusive, especially by including/recruiting a small number of people from underrepresented groups, only to give the appearance of sexual, racial, and other forms of equality and fair treatment within a workforce or other space, without any meaningful commitment to real inclusion and change.

Probably the most familiar way tokenism shows up is racial tokenism in film and TV, through the casting/writing of one BIPOC character. The token BIPOC character is usually not a leading role and often fits into one of several common stereotypes such as the ‘sassy black friend.’ This type of tokenism is not exclusive to racial tokenism. In male dominated casts there may be a token woman. LGBTQ characters are often portrayed tokenistically with only one token gay character who is usually ultra fem or flamboyant if it is a gay man, or, if it is a gay woman, usually either ultra-masculine or ‘butch’ or else hypersexualised/fetishized.

But the one-token-person example isn’t enough to truly understand tokenism, because tokenism can also happen even when there does appear to be a lot of representation. An example of this is when an organisation uses marketing images to reflect diversity, without having inclusive policies to back up the impression of inclusion being given. The key determining factor for tokenism is whether or not efforts to improve representation are backed up by good faith work towards social justice and inclusion… Or is it just representation for representation’s sake?

How can tokenism happen through attempts to improve representation in school?

Tokenism is likely at play if attempts to diversify and improve representation in the curriculum meet any of the following criteria:

They are singular changes, not part of a greater plan/structure (think tick-box exercises)

They only include depictions of members of a particular group in relation to the oppression or marginalization of that particular group (only showing civil rights activists for black representation, or celebrating those with disabilities simply for existing and not for any particular achievements)

They reinforce harmful or condescending stereotypes

The clip from 10 Things I Hate About You referenced above is a particularly interesting and ironic example because the scripting of the Mr. Morgan character is used to make a very important point about the way institutional racism functions through lack of representation in education in the US. Yet, at the same time, the casting of Mr. Morgan is completely tokenistic!

Not only is he one of the only black people in a predominantly white cast, but the character clearly only exists in the storyline for the sake of being black, and whilst he is not portrayed in a condescending manner, he is portrayed stereotypically. If you glance back at those three bullet points above, you can see that the Mr. Morgan character ticks all three criteria.

And while his role in the film is positive in some ways, it is notable that none of the core characters in the film are black, and the only other black character – Bianca’s (Larisa Oleynik) best friend Chastity (Gabrielle Union) – is also largely tokenistic and stereotypical, as an opportunistic mean girl, whose character never evolves throughout the film, and seemingly only exists to support Bianca’s character evolution.

The Mr. Morgan character in 10 Things I Hate About You does, at least, provide some positive representation in his role as a teacher, and the scripting of the character directly challenges the lack of representation of black authors in American education. But it is tokenistic that this point can only be made by a black character (despite the predominant exclusion of black actors in the cast), and that this character is written in alignment with certain racial stereotypes.

You might be thinking, ‘this seems to be a fine line!’ That’s the point… 10 Things I Hate About You was likely ahead of the curve in 1999, with this witty commentary on institutionalized racism and patriarchy in education, but it still stumbled into tokenistic portrayals.

Teachers need to do everything they can to both improve representation and avoid tokenism in schools. And this can be a fine line to walk. Because unfortunately, there are a lot of ways that efforts to increase diversity/representation can go wrong…

Examples of tokenistic representation in schools:

Adding books by authors from marginalized groups not based on the quality of the book, but just to tick a box

Having a multicultural day or teaching a multicultural lesson, but only showing other cultures in condescending, primitive, or exotified ways

Adding books written by BIPOC authors, but only those that are written about race

Teaching about marginalized figures in history and modern/social studies, but only those perceived to ‘breaking stereotypes’ (stereotypes that are imposed on them by the dominant culture)

Teaching about BIPOC historical figures, but only those involved in antiracism, civil rights, or other race-related issues.

Teaching about people living with disabilities in a way that exalts them simply for existing and not for any particular achievement. (Calling them ‘so brave’ or ‘so resilient,’ etc.)

Praising/spotlighting/honouring/awarding pupils with disabilities for no reason or achievement other than existing

Asking for opinions from pupils from marginalized groups and then taking those perspectives as representing the whole group. (Watch out for terms like ‘pupil voice’ in relation to single pupils being asked to speak on behalf of large groups)

A note on that last one- yes, of course, we want to make sure pupil voice is represented in schools, but what we often see is this becoming tokenistic when the bare minimum is done to actually represent all pupils within that voice or to actually act on that voice. In these cases, one pupil may be used to represent pupil voice for many; they may be showcased and spotlit and asked to participate in adult activities, but the actual impact is superficial, and doesn’t actually lead to any real change among school policy and staff behaviours. This lack of real change (but excess of ‘fuss’ being made!) is a tell-tale sign of tokenism.

So how do we improve representation whilst also avoiding tokenism?

Taking racial representation as an example, the following four tips can be used to help improve representation whilst avoiding tokenism:

Include a diverse range of authors and perspectives in classical literature studied and other reading.

Cover a diverse range of role models and significant historical figures.

Study of BIPOC figures is not limited to race specific topics, but includes achievements in a range of areas such as science, maths, philosophy, and writing.

BIPOC figures are not presented as representing their entire culture, country or race.

These same 4 principles could be applied to other marginalized groups as well. If we consider these four points, the first two are essentially the obvious ways to increase representation and diversity in learning content. Points 3 and 4 are then strategies to help check that you’re not doing so in a tokenistic way.

But by far the most important thing educators can do to avoid tokenism, is to take a wholistic approach to inclusion and representation. So, not just applying a few tips and tricks to try to diversify, but actually making sure there is a united, whole-school effort to learn and think critically about representation and inclusion in the curriculum, teaching, policy, and culture of the school.

If schools and educators don’t tackle inclusion and social justice using a wholistic and intersectional approach that focuses on curriculum, policy, and culture, then there is a good chance that any attempts improve diversity and representation will be superficial and veer into tokenism.

Do it right by:

Taking a critical and proactive approach to curriculum and teaching (antiracist education, decolonising the curriculum, combatting gender stereotypes, etc.)

Addressing microaggressions between pupils

Developing awareness of unconscious bias among staff

Developing understanding of microaggressions among staff and learning to reframe and avoid them.

Setting up systems of support for marginalised pupils

Spreading awareness of issues among staff and pupil body

Staying committed to individual personal learning

Okay, so pointing out all the ways good intentions can go wrong might seem a little disheartening, but this doesn’t have to be the case. Instead, this can be empowering. There tends to be an apprehension to confront issues like race and gender in schools, because many teachers don’t feel their knowledge of the issues is strong enough.

But rather than feeling fear or intimidation when we, as teachers, become aware that there’s a lot we don’t know about something, we should instead feel inspired that the most important thing for us to do is LEARN! Learn, listen, share, and start dialogues in your schools. Get actions going! Most importantly, let the kids know you’re there for them, that you care about ALL of them, and that if any of the staff ever do get it wrong, there will be a united approach to doing better and making it right.

Upcoming Webinar:

Representation without Tokenism in Schools: A Workshop for Educators - 29th March 2021 16:30-17:45 BST

Other Useful Resources:

Be sure to check out the Eager Free Resources Library for loads of resources to help teachers (and everyone else!) work towards social justice and inclusion!

Watch the full 10 Things I Hate About You clip here: