On Being In-Between and Nowhere: Why Biphobia is So Damaging... and More Common than You Thought

Words Matter

This month is Pride Month, and while we’ve come a long way since the Stonewall Riots of 1969, we still have a long way to go on the road for justice, equity, and inclusion of all LGBTQIA+ folks. And I don’t mean just from outside the community. Unfortunately, the Pride movement has not always been inclusive, with trans exclusion from queer radical feminists and conflicts between lesbian feminists and gay men over misogyny and exclusion dating back to its origin (not to mention racism, ablism, and other forms of exclusion as well). These conflicts still exist today, but I think it’s safe to say that, overall, the movement has become a much more inclusive space than it was 50 years ago.

But one area that still seems to be a major issue within the queer community (as well as within the mainstream) is biphobia. (To be clear, I’m not saying it’s the only issue, but it’s an issue!)

Biphobia is prejudice against bisexuals and other non-monosexual people. (People who are romantically or sexually attracted to more than one gender.)

Biphobia can affect bisexuals, omnisexuals, pansexuals or anyone of any sort of multisexuality persuasion.

‘Hang on,’ you say, ‘bisexuality, omnisexuality, pansexuality, multisexuality? What do all these terms even mean?’

Don’t worry, I got you... Bisexuality is probably familiar. It is most typically understood to refer to people who are attracted to men and women, but it actually refers to being attracted to two or more genders. So despite the (sometimes misleading) ‘bi’ prefix, bisexuality can extend beyond binary genders.

Pansexuality is when a person can be attracted to anyone, regardless of their gender and omnisexuality means a person is attracted to all genders (the difference here being that pansexuality is sort of gender-blind and omnisexuality is not). All of these fall under the term multisexuality, a general umbrella category that means attracted to more than one gender.

I fall within this umbrella category. I personally don’t mind which specific label is used for me. I can identify with both pansexuality and omnisexuality and have typically identified as bisexual or queer throughout my life to keep things simple. For some people the label is important. For me personally, I don’t really care. I just know that my romantic or sexual attraction to someone is not limited by gender.

In this article, I’m going to use the term bisexual to keep things simple. This is not to discount the distinctions between more specific labels or to exclude those who identify under more specific terms, but because bisexual refers to attraction to two or more genders it can be used as an umbrella term, and it is more familiar than multisexual for most people. There is also more research information available relating to bisexuality, as this is the most commonly used term. (Although it is important to note that research relating to bisexuality will usually include those of other more nuanced orientations under the multisexual umbrella as well, since more specific identifiers often aren’t available when information is gathered.)

So what’s the issue?

Bisexuals are discriminated against by straight people as well as within the LGBTQIA+ community. The forms of discrimination may be subtle, but they are extremely pervasive within society as a whole, and they cause significant harm. In fact, biphobia and other forms of multisexual discrimination are often so widely accepted and normalised within society that it makes them all the more insidious.

As a bisexual myself, even I have internalized some of the biphobic messages I’ve received throughout my life. This internalised biphobia influenced the way I felt about myself and the way I lived my life. They planted false beliefs about myself into my mind. Beliefs like, ‘I shouldn’t broadcast my sexuality because I’ll just look promiscuous or like I’m trying to get attention,’ or, ‘I’m not really part of the queer community because I have straight-passing privilege,’ or, ‘it’s fair for my partner to be concerned about whether I can be faithful since I’m attracted to more than one gender.’ (I feel obliged to clarify that that last one is not about my current partner, but has been an issue in past relationships.) These are all beliefs that I used to have. They are all beliefs that are still commonplace. And they are all absolute and utter nonsense. They are also incredibly isolating and damaging.

Think ‘incredibly isolating and damaging’ sounds like an overstatement? Let’s have a look at the research...

What’s the Impact of Biphobia?

Biphobia comes in many forms (which I’ll detail in the next section), but because they can be a little bit more subtle, you might think that means they are less impactful. This would be a false assumption. Plain and simple. There is significant evidence of the impact of biphobia on multisexual people.

In June of 2019, the Canadian Government conducted an expansive study of LGBTQ inequities and found that bisexuals have higher rates of chronic diseases, poor mental and physical health, and smoking and alcohol use than gay, lesbian and heterosexual people. A 2017 review in The Journal of Sex Research of over a thousand studies, conducted over more than a decade, found that non-monosexual people are the most likely of any sexual minority group to experience depression and anxiety and are the most likely to live in poverty. Another review in 2018 found that bisexuals are at a higher risk of suicide and suicidal ideation than gay, lesbian, or heterosexual people. A 2020 study by the University of Manchester found that bisexual people are more likely to self-harm than those of any other orientation. Studies have even shown that bisexual women have a higher prevalence of developing diabetes and hypertension than lesbians.

So why are poorer health outcomes associated with being bisexual or multisexual? There are a range of potential reasons why, but many of them, while likely contributing factors, are not enough to explain the discrepancies shown in the numbers because they affect others in the queer community as well (for example medical discrimination).

The most likely explanation for these major discrepancies is the minority stress model, which accounts for the way stressors associated with being marginalized build up in a person’s mind and body and cause adverse physical and mental health impacts over time. The minority stress model applies to all minority groups and is particularly relevant in explaining the harmful impacts of microaggressions (small actions or statements, whether in intentional or not, that show discrimination and bias). Microaggressions may be small and unintentional, but they are like small doses of poison that build up in the system over time, gradually causing more and more damage.

So what sorts of minority stressors do bisexuals experience and why is their impact so great? After all, other members of the community will experience minority stressors too, and one of the pervasive biphobic beliefs is that bisexuals experience less stigma than others in the queer community, since we have the option to ‘pass’ for straight. So what’s up with that? Why would minority stressors have a bigger impact on bisexuals? What’s really going on here?

Do Bisexuals Experience Straight-Passing Privilege?

There is a common belief that because bisexuals have the option to be in heterosexual relationships, they therefore possess straight-passing privilege and, according to some, therefore are not really part of the queer community. This is one biphobic belief that has had a major influence on me and on my relationship with the queer community (a relationship in which I’m more often perceived as an ally than someone who belongs, an assumption that, in the past, I often didn’t feel worthy of correcting).

Straight-passing privilege is the idea that if a person’s orientation is perceived to be heterosexual (even though that’s not their real identity) then this protects them from the discrimination faced by non-straight-passing queer people.

As a generally fem, cis-gendered woman, I am not at risk of experiencing hate and bigotry from strangers on the street unless there is some other factor to make my sexuality obvious (e.g. on a date with a woman). I am currently in a relationship with a man and therefore do not experience sexuality-based discrimination as a result of my relationship. We can get married anywhere in the world and do not run the risk of experiencing hate crimes or harassment based on sexual orientation if we show affection in public.

Yes, these are privileges. However, it is very important to note, first of all, that many bisexuals are not straight-passing. Many bisexuals are obviously queer. Many bisexuals are trans. To assume all bisexuals hold straight-passing privilege because they may at any point be in a heterosexual relationship is just false. There are also gay, lesbian, and monosexual trans individuals who are straight-passing. (They may be less likely to have straight-passing relationships, but they can still experience straight-passing privilege in many situations throughout daily life.)

But more to the point, even for those of us who do experience some privileges relating to the visibility of our queerness, this doesn’t make us immune to other forms of marginalisation and discrimination based on our sexuality. Because as soon as we are out to anyone in our lives, any perceived privilege associated with our straight-passing appearance disappears. Straight-passing privilege may stop an out queer person from being harassed in the street, but it doesn’t stop them from being disowned by homophobic family members, discriminated against at work, by doctors, when finding housing with a partner, or in any number of other ways.

Furthermore, the idea that it is in fact a privilege to be straight-passing is debatable. Don’t get me wrong, I get that as a straight-passing cis woman I’m less likely to be targeted for a hate crime while walking home than, for example, a visibly queer trans woman, or an obviously femme gay man or boy. I know I might have escaped certain forms of overt bullying in high school that many queer kids face. I recognise that these are privileges. However, to be ‘straight-passing’ essentially means that even once you’re out, you continue to be viewed as straight by both straight and queer people. This is erasure. This is invisibility. This means having to come out again and again and again and still living your whole life in the closet. And anyone who knows the emotional toll that staying in the closet takes, should understand that this is not a privilege.

Bisexual privilege is a myth. While there are some privileges that some queer people experience in relation to being straight-passing, these privileges are not exclusive to bisexuals, are not extended to all bisexuals, do not create immunity from all sexuality-based discrimination and, regardless, the reality of being queer and straight-passing can actually create further marginalisation and contribute to minority stressors through the invisibility and isolation it creates.

The belief that bisexuals hold straight-passing privilege actually contributes to some of the most malignant forms of minority stressors for bisexuals, because it excludes us from the queer community.

I had an ex-girlfriend tell me that as a bisexual, I was not a part of the community when I wasn’t in a lesbian relationship. She said I was gay when I was in a lesbian relationship and I was straight when I was in a straight relationship, and that was just the way the community worked. Because as long as I wasn’t in a lesbian relationship I was privileged. I wasn’t part of the struggle. Meanwhile, straight people in my life rejected my bisexuality as ‘just a phase’ or ‘just something I was doing for attention’ when I first came out. The fact that bisexuals typically experience exclusion and discrimination from both straight people and within the queer community can leave many of us feeling constantly on the outside, in a sort of void between worlds, without a community that accepts us in our entirety.

This invisible, purgatory-like existence is a serious minority stressor. So regardless of whatever privileges some of us may sometimes experience as a result of straight-passing appearance or relationships, our overall experience of our sexuality is not privileged.

What kinds of discrimination and minority stressors DO bisexuals experience?

There are several ways that bisexuals and other multisexual folx specifically experience discrimination and minority stressors. We touched on a few of them in the discussion above. But here’s a breakdown of some of the key issues:

1. Bisexual Erasure or Bisexual Invisibility: The tendency to ignore, remove or undermine bisexuality, and in some cases, all out denial that bisexuality (or other forms of multisexuality) even exist.

This type of biphobia is extremely common. We see it through statements that invalidate bisexuality. These statements are common in both mainstream and queer culture and media.

Examples...

“You’re just not out of the closet yet.” This trope is especially common for bisexual men. Bisexual men are often externally identified as gay, rather than bisexual, regardless of how they self-identify.

Blatant biphobia by Carrie Bradshaw in Sex and the City.

“You’re just going through a phase.” This old chestnut. Do I even need to elaborate on this one? I suppose I do since it’s still so common. But the absurdity of categorising an entire sexuality as ‘a phase’ just honestly baffles me. Do straight people go through gay phases and vice versa? This is not how it works! (Insert facepalm.)

“You’re just confused.” Many queer kids, including those who are gay/lesbian, hear this one when they first begin coming out or exploring their sexuality, but bisexuals are particularly vulnerable because they hear it from homophobes and queer peers alike, and it often doesn’t stop even once they’re fully out.

“You’re just greedy.” Umm, okay, straight and gay people... If bisexuals are just greedy because we’re attracted to more than one gender, are you all just picky and prejudiced for only being attracted to one?

“Pick a side.” Um, again, straight and gay people – Did you ‘pick’ your side???

“You’re just doing it for attention.” This one is especially common for young bisexual women and correlates with a tendency to sexualise bisexual women and girls, a major problem in its own right, which I’ll talk about in greater depth in the next section.

All of these sorts of invalidations come at us from media, friends, family, and even partners. They happen again and again and again. And they take a toll.

2. Oversexualisation of bisexual women and expectation of sexual promiscuity: Bisexual women have been sexualised as a straight man’s fantasy, often accompanied by the expectation that bisexuals are always into threesomes, always non-monogamous, and essentially exist as sexual props, there to add a little something extra to existing relationships. Girls who come out as bisexual are often immediately sexualised by their peers, even at a young age. This is extremely harmful and dehumanizing and can cause significant trauma for young girls who may already be struggling to come to terms with their sexuality anyway.

Bisexuality and promiscuity/sex-drive are completely unrelated. There are bisexuals who are polyamorous (have multiple romantic partners) and bisexuals who are completely monogamous. There are bisexuals who have had many sexual partners and there are bisexuals who don’t engage in premarital sex at all. Because, um, we’re human beings, and we come in just as much variation as anybody else.

For those bisexuals who are open to polyamory, they will often be treated as a ‘unicorn’. A unicorn is a slang term for a bisexual woman who has sex with couples without developing any emotional needs of her own in the relationship. The unicorn phenomenon comes about when couples expect to find a bisexual woman who will happily be a third in their relationship, bringing some excitement and fixing all their existing relationship problems without bringing any emotional needs of her own. (Obviously this does not exist, hence the name, unicorn.) To clarify, I am sex positive and have absolutely no problem with polyamory. There are many people who engage in healthy polyamorous relationships, and this is not meant as any sort of shaming of these people. But the unicorn stereotype is a phenomenon that happens when the bisexual woman is dehumanised and essentially turned into a prop for an existing relationship. This is extremely problematic.

3. Ridiculous Myths, Stereotypes, and Negative Representation in Media: There are some pretty ridiculous myths and stereotypes about bisexuality. We see these narratives being played out again and again in film and media, even among more queer conscious shows and movies; as well as experiencing them first-hand from the people in our lives.

Examples...

Bisexual representation in fiction/film/TV too often writes bisexual characters as one of several tropes:

Indecisive cheater who is bound to cheat with someone of a different gender than their partner

Not-fully-out-of-the-closet gay guy, who only identifies as bisexual as part of a transition to coming out as gay.

Promiscuous bisexual woman, only existing in the plot to join into and/or cause trouble within an existing relationship.

Ridiculous questions and assumptions from people in our lives:

“You’re pansexual... Are you attracted to pans?”

“Are you just attracted to everyone then? How can you have housemates since you’re attracted to all genders? Your friends must not be able to change clothes in front of you because you’d just be perving on them.” This is ridiculous. Being open to relationships with more than one gender does NOT mean that we are attracted to every single person we meet, or that we will creepily perv on our friends. Just like anyone else, bisexuals have platonic friendships. Just because we might romantically connect with someone of the same gender as our bestie, doesn’t mean we’re attracted to our bestie. I really feel like this shouldn’t need to be explained! (Rips hair out a little.)

“You’re just horny/greedy/have an overactive sex drive.” You can be bisexual multisexual without having EVER had a single partner! You can be multisexual without having ever had a same-gender partner. You can be multisexual without having ever had a different-gender partner. Sexual orientation and sex drive are completely unrelated!

The myth that bisexuals can’t ever be monogamous/will always cheat...

You can be bisexual and be in a committed monogamous relationship. Again, this is just SO ridiculous. Let’s just put this into perspective: say you are attracted to people with blonde hair and people with black hair, and then you get into a relationship with someone with black hair. Are you inevitably bound to cheat on them with someone with blonde hair? We shouldn’t have to explain this. Just because it’s possible for you to be attracted to more than one type of person doesn’t mean it’s impossible (or even any harder than it would be for anyone else) to be faithful to one person. This is no different with gender than it is with any other attribute.

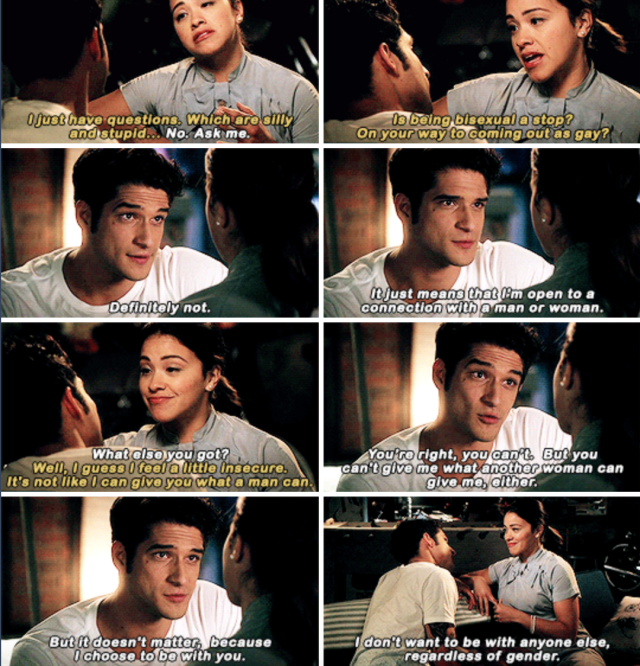

Addressing biphobia in Jane the Virgin.

4. Exclusion from both straight and queer communities: We touched on this in the discussion about the myth of bisexual privilege, but it’s worth a deeper look. When bisexuals come out to straight people in their lives, they run the same risk as gay and lesbian folx of being overtly rejected, discriminated against, and excluded. Additionally, however, when bisexuals come out within the queer community, they run the risk of being rejected, discriminated against, and excluded there too.

When my ex-girlfriend told me I was only in the community when I was in a gay relationship, she didn’t mean it to be hurtful. But the message was the same: You don’t belong. You are not accepted. You’re not a part of this club. In some cases, bisexuals can be seen as “traitors to the cause” by gay and lesbian folx. This goes against everything the cause stands for! Love is love! And maybe I’m reaching here, but wouldn’t you think bisexuals and other multisexuals should be the absolute poster children of the Pride movement?! I mean, not to undermine the need for more representation of other marginalised LGBTQIA+ groups or anything, but just saying: Multisexuality represents the sexual orientations in which we love with the least rigidity. Isn’t that what the whole movement is fighting for? Freedom to love who we love? Shouldn’t the ability to love without gender bounds be celebrated?

Key Take-Aways on Discrimination & Minority Stressors Bisexuals Experience

The stigma and erasure associated with biphobia results in minority stressors that occur again and again and again on a regular basis throughout life. (It’s important to note that this impact will be even greater for bisexuals who also receive minority stressors for other parts of their identity that are marginalised, such as race, gender, disability, having a gender other than that assigned at birth, etc.)

Since many of the minority stressors experienced exclusively by bisexuals are microaggressive in nature, they may seem at first to be less impactful, but in fact their more covert or nuanced nature can make them much more insidious. They underpin everything. They lead to a culture in which bisexuals exist in between worlds, never fully accepted by the queer community or the heteronormative mainstream when they are visible, and are more often forcibly made invisible.

Invisibility is a force that creates deep emotional turmoil and trauma for all members of the LGBTQIA+ community. However, for many queer folx, this invisibility is left behind after coming out and/or transitioning. Many queer people describe a strong sense of liberation and freedom after coming out and/or transitioning. It doesn’t mean they won’t continue to experience trauma as a result of homophobia, transphobia, etc., but being ‘out’ for gay and lesbian folx, means being able to live fully in their truth, and often means finding love and acceptance in their new chosen family within the queer community. This can have massive positive impacts on mental and physical health and wellbeing through reducing minority stressors or at least alleviating some of the negative impacts associated with them. This is because it alleviates the ‘invisibility’ factor and provides community, positive relationships, a sense of solidarity, acceptance, and belonging; all of which are massively important for overall wellbeing. For many queer folx coming out means finding a whole community of people who will always remind them that it is ok to be who they are, that who they are is valid. But for many bi and other multisexual folx, this moment never comes. Even after coming out. Because their sexuality continues to be dismissed, discredited, ignored and undermined. The negative health impacts of this should not be underestimated.

Where do we go from here?

The purpose of this article is not to pit bisexuals against the rest of the queer community. On the contrary, I’m advocating for the very acceptance the community has always fought for! Whether a bisexual person is a man, woman, or trans or nonbinary; whether they are straight-passing or not, cis/cis-passing or not, we are all still part of the community. We deserve the same acknowledgement and acceptance as anyone else. Because love is love is love is love!

As I mentioned at the start of this post, I myself have been guilty of biphobic conditioning. I was so used to hearing these messages, I just accepted that I didn’t really deserve to be a part of the community. I wasn’t queer enough. I didn’t count because I was too femme, too privileged. And in straight crowds, I was never closeted, but also didn’t broadcast my sexuality, knowing it would likely just be received as a ‘cry for attention’ or ‘just a phase’ or would have branded me as ‘promiscuous.’ I didn’t realise that I had internalised biphobic messages that I’d experienced, and these were impacting the way I saw myself and expressed my sexuality.

Discrimination at work, from friends, from partners, or in media is wrong. Period. This is the fight we’re fighting, and we need to fight it for all of us. None of us are free until all of us are.

Even those of us like myself who do hold straight-passing privilege, we are still here, and we are still queer! And while we may all be very used to the blatant biphobia in society, that’s not something we should be staying comfortable with.